Our story, Part I: What really happened to school funding?

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| 198.81 KB | |

| 191.33 KB | |

| 192.3 KB |

The election's over - can we talk reality now?

For a while, it was gratifying that school funding issues took center stage in the recent election for Michigan's governor. Unfortunately, the amount of spin and, well, dishonesty, left the situation more confusing than before. Now that the election is over, our choices about school funding need to be based on facts, not confusion.

Here are three basic facts that everyone needs to understand. The evidence for them is indisputable:

- Starting with the 2012 fiscal year, the Governor and Legislature together took away roughly $1 billion that would normally have gone to K-12 education. That loss has been repeated each year since then, adding up to billions of dollars missing from school aid.

- Schools took a major cut that first year, but they didn't have to: the state's economists had predicted revenues would have allowed schools to keep their funding level even as Federal stimulus money expired. The tax cuts that year made the school cuts necessary.

- The slow growth in school funding since that first year had nothing to do with the Governor or Legislature or any decisions they made. It's all the result of automatic systems which collected more funds for schools as the economy recovered.

"Come again?" you might say. That's not what we were hearing from all the campaign commercials. But it's the reality we need to come to terms with. So let's go over it in a little more detail.

In their first budget together, Gov. Snyder and the Legislature chose to phase out the Michigan Business Tax (MBT) without replacing most of it - thus ending an earmark that would have contributed $740 million to the School Aid Fund in the 2011-12 fiscal year alone. They also chose to shift a net $277 million in community college and state university costs into the School Aid Fund, removing that money from K-12 funding. Total diversion away from K-12: over $1 billion in the first year (FY2012). (See chart at left. Click on charts to see full size images.)

In their first budget together, Gov. Snyder and the Legislature chose to phase out the Michigan Business Tax (MBT) without replacing most of it - thus ending an earmark that would have contributed $740 million to the School Aid Fund in the 2011-12 fiscal year alone. They also chose to shift a net $277 million in community college and state university costs into the School Aid Fund, removing that money from K-12 funding. Total diversion away from K-12: over $1 billion in the first year (FY2012). (See chart at left. Click on charts to see full size images.)

- In that same budget, school districts took a $470 per pupil cut. This cut was not made necessary by the end of Federal stimulus funds. In fact, in January 2011 top state economists projected that revenue into the School Aid Fund would allow the state to restore school funding to 2008-09 levels despite the end of the stimulus payments. (This was before the Governor's first budget proposal was announced.) The cuts were made necessary largely by the end of MBT revenue and the money shift to higher education.

- Even after all these reductions, revenue to the School Aid Fund has slowly recovered as the economy recovered - most of it comes from the sales tax and the state income tax. This revenue, and the slow recovery, was all automatic and not due at all to any actions by lawmakers in Lansing. (Unless you want to give credit for the recovery to Lansing, but other states that chose different policies also recovered at least as quickly.) So, yes: from FY2010 to FY2015, covering Gov. Snyder's first term, revenue to the School Aid Fund rose by $1.04 billion. But, if the 2011 tax cuts had not taken place, revenue to the SAF would have risen by $1.75 billion (House Fiscal Agency estimates). And if the diversion to higher education had not been made a permanent part of the budget, K-12 education would have benefited from that entire amount - minus, of course, the rising mandatory pension payments.

These dramatic changes from four years ago were layered on top of other, longer term, problems that were squeezing school funding.

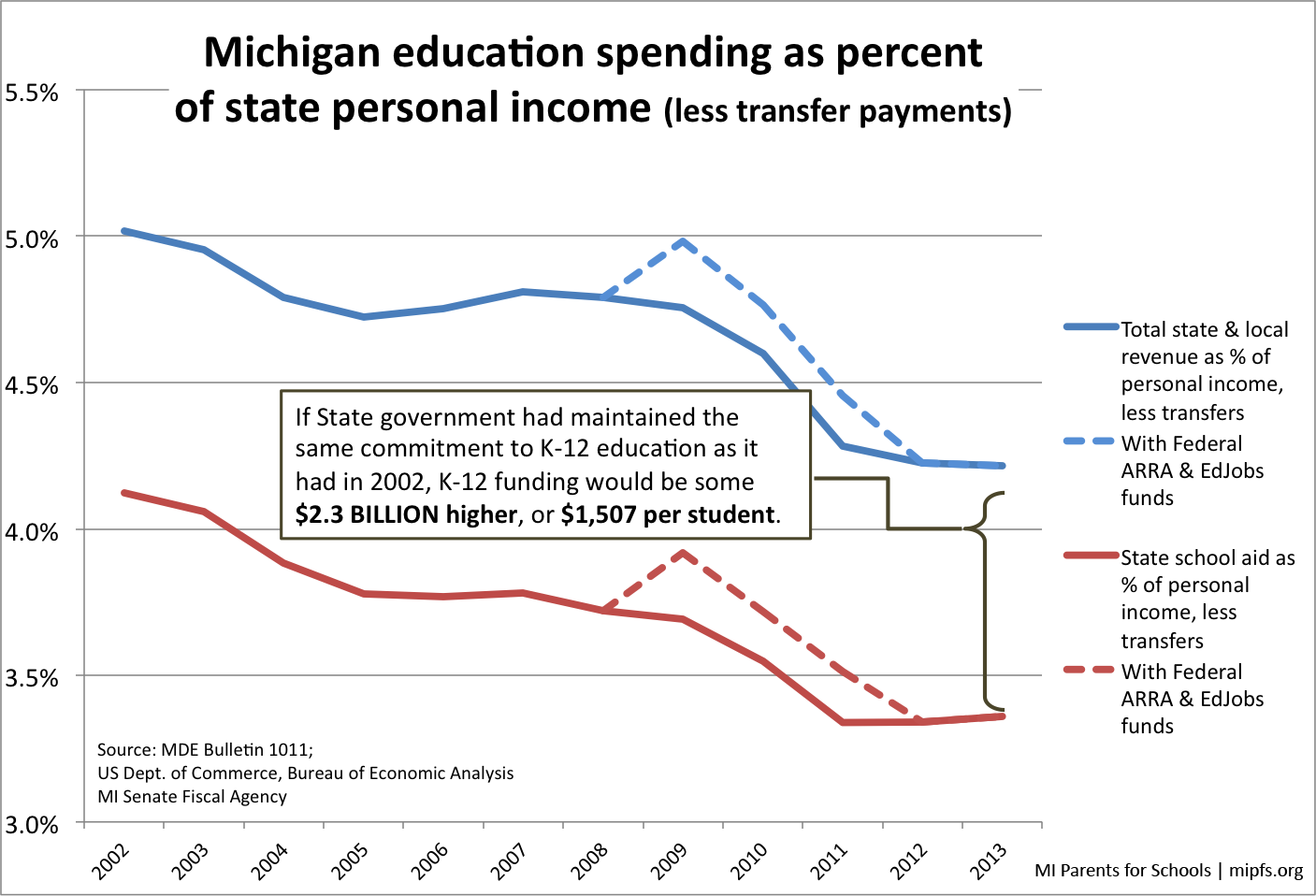

For a decade, the percentage of our state's economy that we invest in K-12 education has been dropping - in good times and bad, we have been committing less to education. Had we just kept the fraction the same, we would have over $1 billion more for schools today. (See chart at right.)

For a decade, the percentage of our state's economy that we invest in K-12 education has been dropping - in good times and bad, we have been committing less to education. Had we just kept the fraction the same, we would have over $1 billion more for schools today. (See chart at right.)

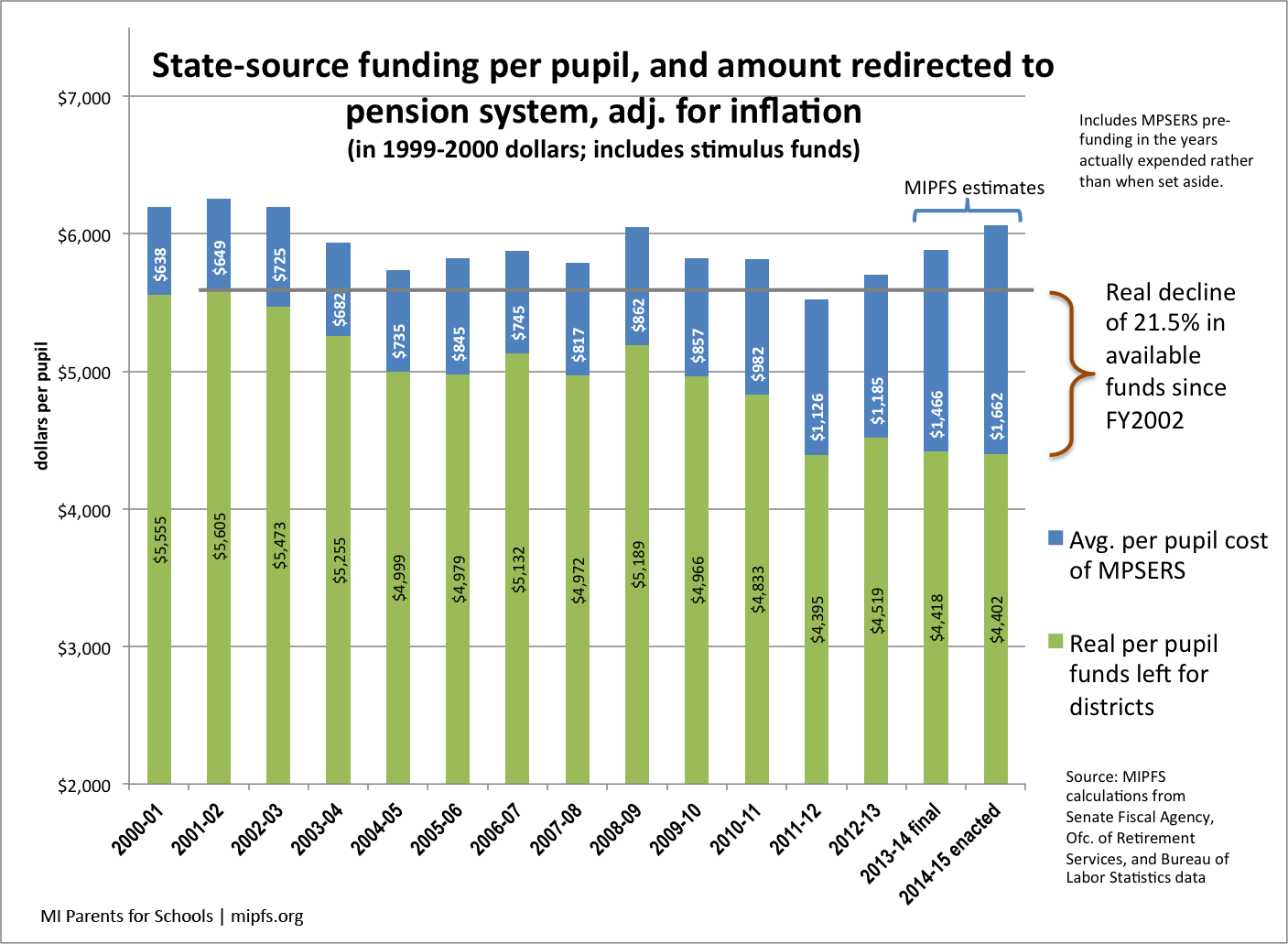

- The amount of money available to actually run schools has been declining, after adjusting for inflation, once you take away the money which schools must pay into the state school employee pension system. Real (inflation-adjusted) per pupil dollars available for school operations is down 22% in the last 12 years. (See chart at left.)

This is not at all to argue that we should not honor our promises to the folks who have taught and cared for our children. But the costs of the stock market crash, which hit the pension system's investment portfolio hard, are being borne entirely by current students and current employees. Should our kids' education depend on the whims of Wall Street?

This is not at all to argue that we should not honor our promises to the folks who have taught and cared for our children. But the costs of the stock market crash, which hit the pension system's investment portfolio hard, are being borne entirely by current students and current employees. Should our kids' education depend on the whims of Wall Street?

Details on these last two points are in the charts included at the end of this article. Below, we reprint an opinion piece written before the election that tries to set the record straight on school funding. The elections are over, but it is never too late for the truth to shape the future.

---------------------------------------

While a recent article in the Detroit Free Press (“Freep Fact Check,” 9/29/14) holds that Gov. Snyder is correct in saying he did not cut K-12 education spending, the reality is more complex. In his first budget, Gov. Snyder proposed tax changes that would dramatically change the level and source of state revenue. Did the governor and the legislature remove roughly $1 billion of K-12 school spending that was already budgeted? No. But did the governor and legislature prevent $1 billion from going to K-12 that otherwise would have by law? Absolutely. So it all depends on how you define the word “cut.”

One thing that’s important to remember about school funding in Michigan is that nearly all school aid revenue are automatic – we’ve set the taxes in place, and the funds are committed to schools. Lawmakers can play with exactly how those monies are spent, but the size of the pot is usually not in question. The only exceptions to this are: the amount contributed from the state’s General Fund budget to K-12; and the structure and rates of the taxes which feed into the School Aid Fund. And that’s what changed in the late winter of 2011.

In their December 2010 appraisal of the Michigan economy and state revenues, the nonpartisan Senate Fiscal Agency projected that revenues to the School Aid Fund for Fiscal Year 2011-12 (the next budget) would allow per-pupil school spending to return to 2008-09 levels. This would not be an actual increase, since the drop in between had been mostly covered by Federal stimulus funds. But the SFA said that projected revenue would allow that Federal money to be replaced. Both the House agency and the Treasury had similar numbers.

Roughly two months later, Gov. Snyder proposed a budget package that replaced the Michigan Business Tax with the new, lower, Corporate Income Tax. The budget also moved hundreds of millions in community college and university spending into the School Aid Fund, offset with a much smaller amount of general budget money.

Whatever the issues with the MBT, it did have a portion dedicated to school aid, which would have been worth roughly $740 million in 2011-12, according to the fiscal agencies. When the MBT was phased out, that money was not replaced. The School Aid Fund would be missing that money every year, basically forever.

At the same time, the final version of the budget moved $396 million in higher education spending out of the general fund, offset by only $119 million in transfers from that budget. This meant a net reduction of $277 million in the money available to K-12. That pattern has continued in the years since. Where does that leave us? About $1 billion short, each year.

In that first year, schools took a $470 per-pupil hit. Michigan’s economy was recovering – enough that revenues available to K-12 actually started to inch up despite all these changes. But inflation-adjusted school spending per pupil did not return to 2008 levels until this school year. That money includes funds dedicated to paying the cost of the state school employee pension system (MPSERS). When the increasing cost of MPSERS – because of investment losses and fewer participants – is factored in, the money available after inflation for school operations is at its lowest point since the turn of the century and some 22% lower than in 2002.

A few years ago, there was much talk of “shared sacrifice” as Michigan’s budget problems were being tackled. But the sacrifice was only shared by some. It’s possible to argue that this is what Michigan needed (though many would disagree): that lowering business taxes at the expense of school funding made the most sense. But instead of arguing the policy, many lawmakers today are busy arguing that none of this happened. That does a disservice to our schools, and distorts the discussions we will need to have as a state about how to invest in education in the future.

Steve Norton is executive director of Michigan Parents for Schools (mipfs.org).