What's up with school funding?

For a fuller discussion of how the school funding system works, and how it came to look this way, check out this article originally posted on one local PTO's online conference. The article reviews the politics behind Proposal A and what's happened since then. It also has links to some very helpful documents. The article is reprinted below, with permission.

Posted October 12, 2006. With the run-up to the November elections and the (muted) buzz about Proposal 5, I thought this would be a good time to wax eloquent a bit about how our schools are funded.

Why can't we?

One of the comments I hear most often about programs at our public schools goes something like, "We're such a well-off community, why can't we have..." and insert your preferred item: smaller classes, more teachers, foreign language, more enrichment, or any of a dozen others. Another thing I hear, more quietly, from many families at Burns Park is, "Do we have to have all the PTO fundraisers?" The answer to the second question is "Yes," and the reason for that answer has a lot to do with the answer to the first question. And for that answer, we need to go back in time a bit - thirteen years to be precise. It's the summer of 1993, and our first term Republican governor, John Engler, is trying to make good on the principal plank of his election campaign platform - to reduce property taxes. The new legislature is eager to help. As Cullen and Loeb (2004) put it:

On July 20, 1993, the state senate was debating Governor Engler's latest proposal to reduce property taxes. [Then-State] Senator Debbie Stabenow proposed an amendment to entirely eliminate the property tax as a source of local school finance, a move widely interpreted as an attempt to show how impractical it was to cut taxes without specifying new revenues for schools. Surprisingly, the senate passed the amended bill the same day, the house followed a day later, and the governor signed the bill. With little debate the state had eliminated $6.5 billion in school taxes for the 1994-1995 school year.

It wasn't until the next year before lawmakers had a proposal ready to replace that funding. Actually they had two: one presented to the voters in March 1994 and another that would take effect if the proposal failed. The ballot proposal would increase the sales tax by two percent (to 6%) - the increase earmarked for schools - create a limited state property tax to fund education, add a few other "sin" taxes, and cut income taxes. The alternative relied on increases in the state income taxes to fund schools. Proposal A passed by a 2-1 margin, and carried all of Michigan's counties. (But March elections are a tricky thing: turnout for this special election was about 39% of the registered electorate, as compared to around 51% for the November gubernatorial election later that year.) Part of its appeal was the promise to reduce inequities in school funding, and the implicit promise to increase overall spending on schools. The new system established a "foundation allowance" of state funds paid to each district, defined in dollars per pupil, which would be supported by about three-quarters of sales tax revenue, a new (lower) state property tax for schools, limited local taxes on commercial property, and other taxes. Districts which had been spending very little per pupil would be brought up to a "floor," which would be raised regularly. There were some wrinkles: on the one hand, high-spending districts (such as Ann Arbor) were allowed to levy a "hold harmless" millage on homestead property, which would keep them at their 1993 spending levels regardless of the effect of the new formula. This levy was frozen in dollar-per-pupil terms at 1993 levels, however, so that the tax is reduced as property values increase. On the other hand, the new system also made funding to any district dependent on its total enrollment: a district that was shrinking, or losing students to the new charter schools, would face immediate cuts in state funding. The system certainly did cut property taxes for most of the state, and school funding has become somewhat more equal. And total state support for schools has increased most years in the period since 1994, at least without adjusting for inflation. But the cracks are beginning to not just show, but get wide.

Fast-forward to the present.

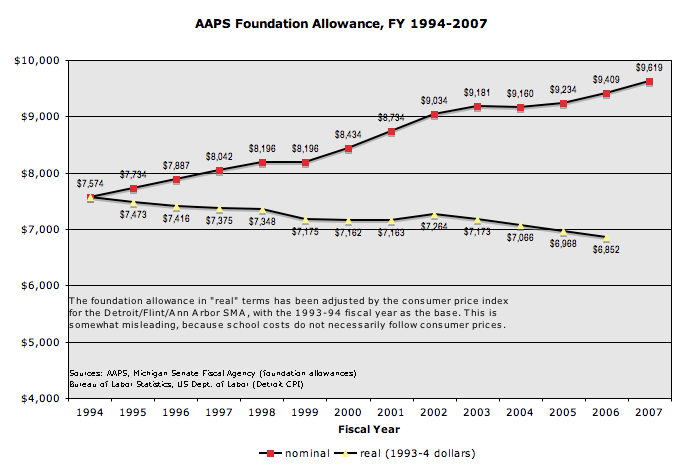

The combination of ongoing deficits in the state budget, a constitutional requirement of a balanced budget, and overall tax limitations set by the "Headlee Amendment" have made funding for education more of a gamble. While the state was able to expand funding in the late 1990s, a substantial portion of the funds provided by the state are not guaranteed and can vary depending on revenue collection. With school funding now heavily dependent on sales tax and similar revenues, which are generally much more sensitive to economic conditions than property taxes, the overall funds available for education are more variable. (The changes have been a kind of one-two punch for most school districts. More than half of the revenue for the school aid fund comes from sales tax revenue, and a further 20% comes from the income tax, with only 20% coming from the state education property tax. This puts the vast majority of state education revenue sources on taxes that are highly sensitive to economic conditions. Moreover, the taxable value of homestead property was decoupled from its "SEV;" taxable value can only rise at the lesser of the rate of inflation or 5%. As a result, taxable value of homestead property has significantly lagged SEV state-wide. Taxable value does catch up with SEV when the property is sold, however.) At the same time, the school funding formulas after Proposal A build in a damper on high-spending districts in an effort to promote equity; spending differences are far from eliminated, but growth in per-pupil spending in districts like Ann Arbor has been sharply curtailed. The real value of the allowed per-pupil spending in Ann Arbor has stagnated and fallen slightly since fiscal 1994, once inflation is taken into account (see chart). Moreover, the student population of the AAPS has leveled off over the last few years - and since state aid is based on a per-pupil allowance, that means funding has leveled off as well.  And while some districts were able to stash some money away after the Durant settlement (which awarded districts compensation for special education programs they had been required to fund), Ann Arbor used that money to pay part of their obligations resulting from the substitute teacher lawsuit. (The cost of those obligations, to former substitute teachers who were not treated as required by law and the union contract, finally amounted to some $31 million; the district settled a malpractice suit against the law firm which had advised them on this matter for $6.8 million, leaving the rest to come from the district's general fund.) A side note: while school operating funds are regulated by the Proposal A rules, school capital budgets are not. So Ann Arbor is free to vote taxes to pay for a new high school, for example, but not to staff it.

And while some districts were able to stash some money away after the Durant settlement (which awarded districts compensation for special education programs they had been required to fund), Ann Arbor used that money to pay part of their obligations resulting from the substitute teacher lawsuit. (The cost of those obligations, to former substitute teachers who were not treated as required by law and the union contract, finally amounted to some $31 million; the district settled a malpractice suit against the law firm which had advised them on this matter for $6.8 million, leaving the rest to come from the district's general fund.) A side note: while school operating funds are regulated by the Proposal A rules, school capital budgets are not. So Ann Arbor is free to vote taxes to pay for a new high school, for example, but not to staff it.

Here we are

School operating funds for Ann Arbor are essentially set by the Legislature, and are dependent on the revenue which the state collects with taxes dedicated to education. Shortfalls in those taxes can (and have been) filled with transfers from the state's General Fund, but with the state budget in deficit this is less likely to happen. (In fiscal 2003 and 2004, in fact, state payments to schools were "prorated" - cut - mid year to reflect lower than anticipated revenue collection.) The "hold harmless" taxes we were allowed to levy in order to stay at our original spending level have been frozen at the same absolute level (per pupil) for the last thirteen years. So while the AAPS can decide, within limits, how to spend the money allocated, the amount of money available is determined by the Legislature and the size of our student population. This is part of the answer to the "Why can't we....?" question. Between state funding issues and local financial troubles, the AAPS has had to tighten its belt repeatedly over the last several years. Among other things, this has meant upward pressures on class size, and shrinking district funding for enrichment activities and instructional support. The bulk of PTO funding each year goes to cover costs which used to be paid by the district: materials subsidies for classroom and specials teachers; enrichment activities for students, especially in lower elementary classes; support programs such as "Books on Tape;" etc. To continue to fill this gap, the PTO works hard to raise funds each year, even at the risk of becoming annoying at times. As to the bigger picture, school funding is affected by decisions in Lansing even more than decisions here in Ann Arbor. Keep this in mind as you consider candidates for the state legislature this November.

A Note about Foundation Allowances

The system to calculate foundation allowances after Proposal A is hard to get one's mind around, particularly for high-spending districts which are subject to a lot of special provisions. Basically, it works like this: In the first year under Proposal A (1994-5), the legislature established three reference funding levels which would be used in the state aid formula: a minimum per-pupil allowance, a "basic" allowance for reference, and a maximum allowance. The minimum was $4200, the "basic" was $5000, and the maximum was $6500. In general, in the first year districts received funds that matched their per pupil spending from the year before Proposal A plus a fixed increase (more for lower-spending districts, less for higher-spending ones). There were exceptions: districts which had been spending less than $4200 per pupil before Proposal A had their funding from the state raised to this "floor." Districts which had been spending more than $6500 in the year before Proposal A were allowed to levy local taxes on homestead property to bring them back up to their 1993-4 spending levels (the "hold harmless" millage). These millages were fixed at this dollar-per-pupil level in perpetuity, so the actual tax rate needs to be adjusted each year to make sure it collects the same dollar amount per pupil. (For instance, Ann Arbor had spent $7734 per pupil in 1993-4, so in the first year of the new system we received $6500 from the state -the maximum - and were allowed to levy additional local taxes to raise the remaining $1234 per pupil. The district continues to levy this tax, but is limited to collecting enough money to raise $1234 per pupil each year. This figure is not adjusted for inflation.) In subsequent years, the legislature would make increases in the "basic" foundation allowance that reflected changes in the amount of revenue collected by the state. Districts at or above the new "basic" allowance level would receive funding increases equal to the dollar value of the increase in the basic allowance. The minimum allowance ("floor") was raised in tandem with the basic allowance, but by double the amount of the rise in the basic; districts which had allowances between the minimum and basic levels received double the dollar increase of the basic. (For instance, for 1995-6, the basic allowance rose from $5000 to $5153, an increase of $153. The minimum allowance rose by twice that, $306, to $4506. Districts above the floor but below the basic received a $306 increase in their allowance. Districts at or above the basic level received a $153 increase in their allowance.) Some changes were made as time went on. For the 1999-2000 year, the minimum allowance was made equal to the basic and all districts were brought up to that level. After that point, all districts received the same increase each year, if any. Starting with the 2002-3 fiscal year, the maximum allowance was kept to only $1300 above the basic, down from $1500, effectively cutting $200 per pupil of the funding increases for high-spending districts. Finally, the school aid act was amended with a provision to compensate districts which had to roll back tax levels because of a "Headlee override," and so could not generate the revenue needed to reach their target funding in any one year (called "20j hold harmless" contributions). State school aid payments can be reduced, or "prorated," if revenue projections turn out to have been too high.

Articles worth reading:

Downloadable copies of these articles are linked below; copyright remains with the original authors and/or publishers. Cullen, Julie Berry and Susanna Loeb, "School Finance Reform in Michigan: Evaluating Proposal A," in John Yinger and William Duncombe (eds.), Helping Children Left Behind: State Aid and the Pursuit of Educational Equity, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2004. State of Michigan, Department of the Treasury, Office of Revenue and Tax Analysis, "School Finance Reform in Michigan - Proposal A: A Retrospective," prepared by Andrew Lockwood, December 2002. Arsen, David and David N. Plank, "Michigan School Finance Under Proposal A: State Control, Local Consequences," State Tax Notes, Vol. 31, No. 11, March 15, 2004. Summers-Coty, Kathryn, Proposal A: Are We Better Off? A Ten-Year Analysis 1993-94 Through 2003-04 Senate Fiscal Agency Issue paper, June 2004. Ann Arbor Public Schools, "Understanding the School Budget (FY 2004-5)", 23 June 2004.

- Log in to post comments